Introduction

Bioluminescence is the emission of light during a chemiluminescence reaction by living organisms.

Bioluminescence occurs in multifarious organisms ranging from marine vertebrates and invertebrates,

as well as in some fungi, microorganisms including some bioluminescent bacteria, dinoflagellates and

terrestrial arthropods such as fireflies.

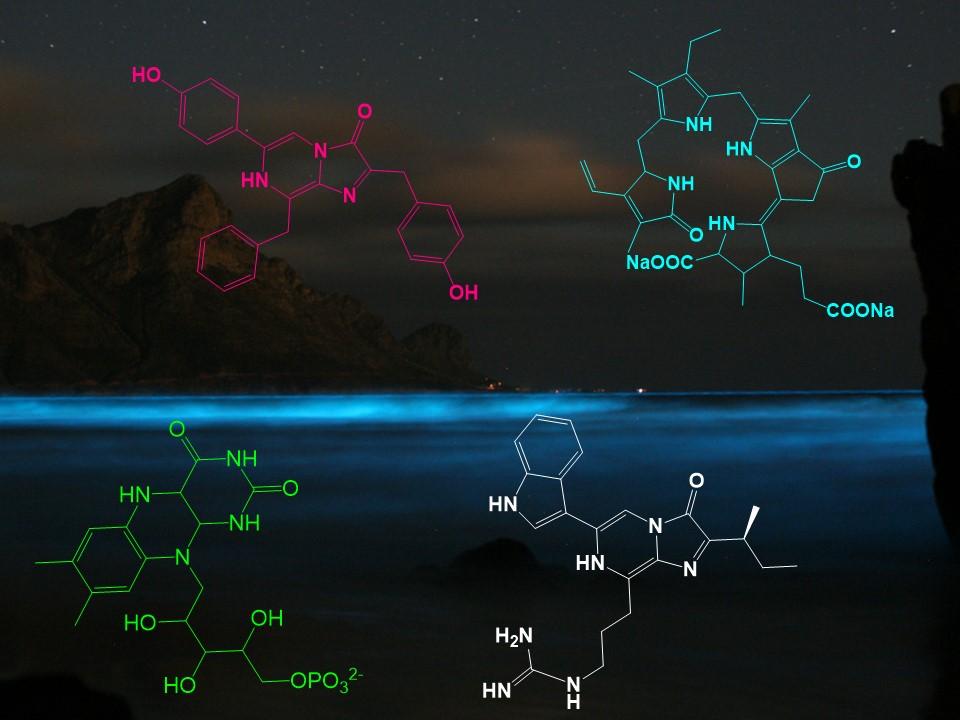

In most cases, the principal chemical reaction in bioluminescence involves the reaction of a substrate

called luciferin and an enzyme, called luciferase. In all characterized cases, the enzyme catalyzes the

oxidation of the luciferin resulting in excited state oxyluciferin, which is the light emitter of the reaction.

In evolution, luciferins vary little: one in particular, coelenterazine, is found in 11 different animal phyla.

Conversely, luciferases vary widely between different species. Bioluminescence has arisen over 40 times in

evolutionary history.

700+

Animal Genera Can Glow

76%

Of Deep Sea Animals Glow

40

Times It Evolved Independently

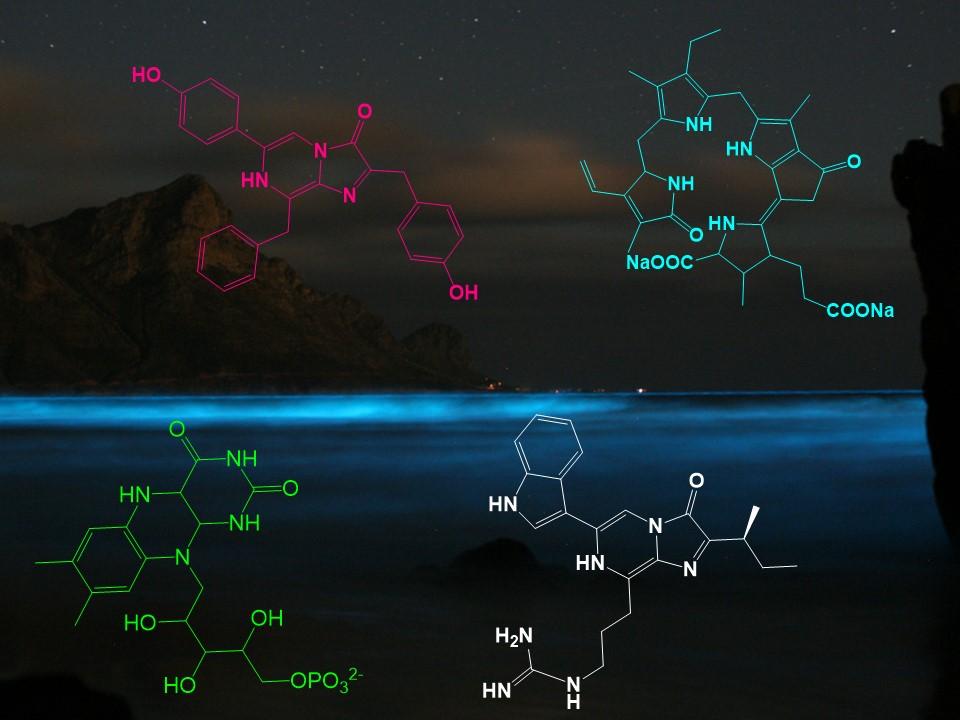

Different types of luciferin molecules found in various bioluminescent organisms. When oxidized by luciferase enzymes, these molecules produce light.

Bioluminescent Organisms

Bioluminescence occurs widely among animals, especially in the open sea, including fish, jellyfish,

comb jellies, crustaceans, and cephalopod molluscs; in some fungi and bacteria; and in various

terrestrial invertebrates. More than 700 animal genera have been recorded with light-producing species.

In marine coastal habitats, about 2.5% of organisms are estimated to be bioluminescent, whereas in

pelagic habitats in the eastern Pacific, about 76% of the main taxa of deep-sea animals have been found

to be capable of producing light.

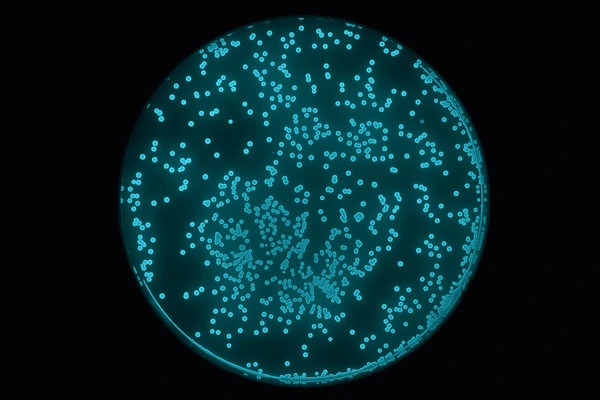

Dinoflagellates

The most frequently encountered bioluminescent organisms in the surface layers of the sea,

responsible for the sparkling luminescence sometimes seen at night in disturbed water. At least

18 genera of these phytoplankton exhibit luminosity.

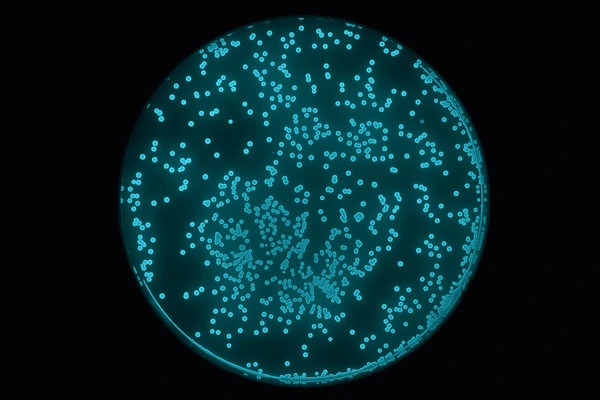

Bacterial Symbioses

Most luminous bacteria inhabit the sea, dominated by Photobacterium and Vibrio. Many are found

in symbiotic relationships that involve fish, squids, crustaceans as hosts.

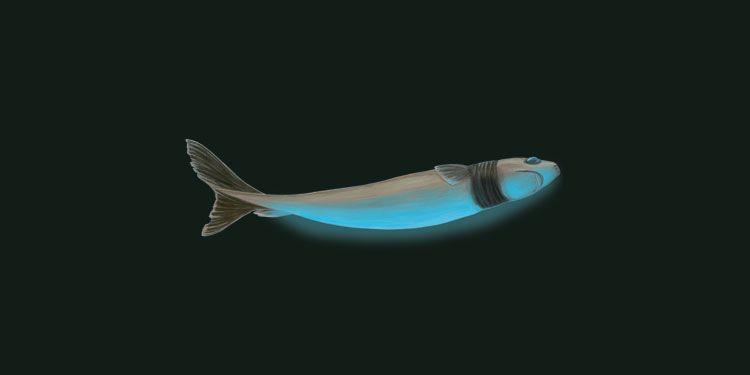

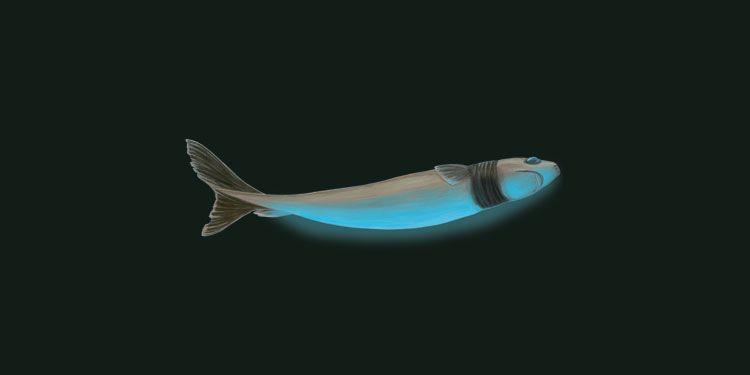

Deep-Sea Fish

About 1,500 fish species are known to be bioluminescent; the capability evolved independently

at least 27 times. They use light to lure prey or hide from predators.

Cephalopods

Many cephalopods, including at least 70 genera of squid, are bioluminescent. Some use bacterial

bioluminescence for camouflage by counterillumination.

Fireflies

Fireflies use light to attract mates. In one system, females emit light from their abdomens to

attract males; in the other, flying males emit signals to which the sedentary females respond.

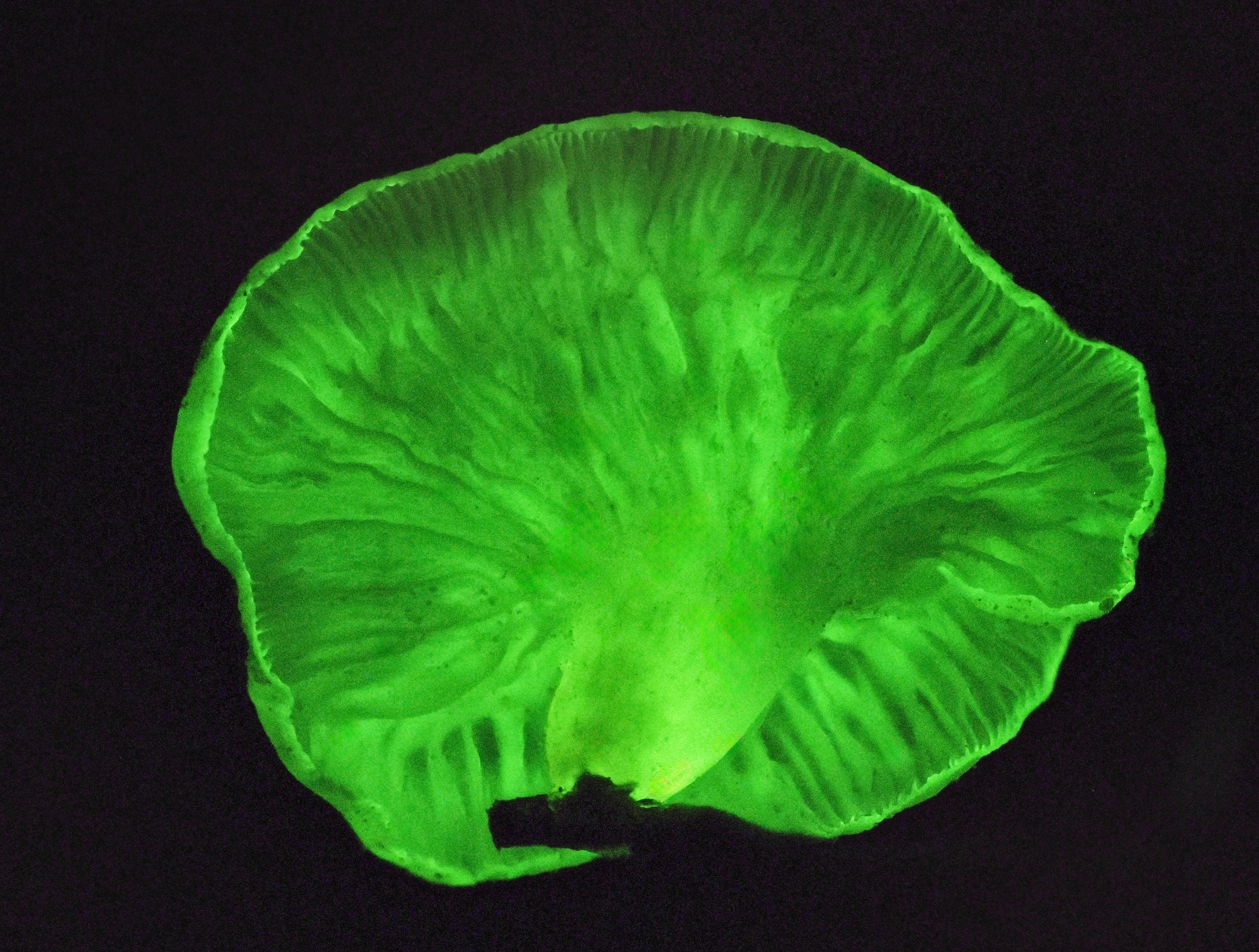

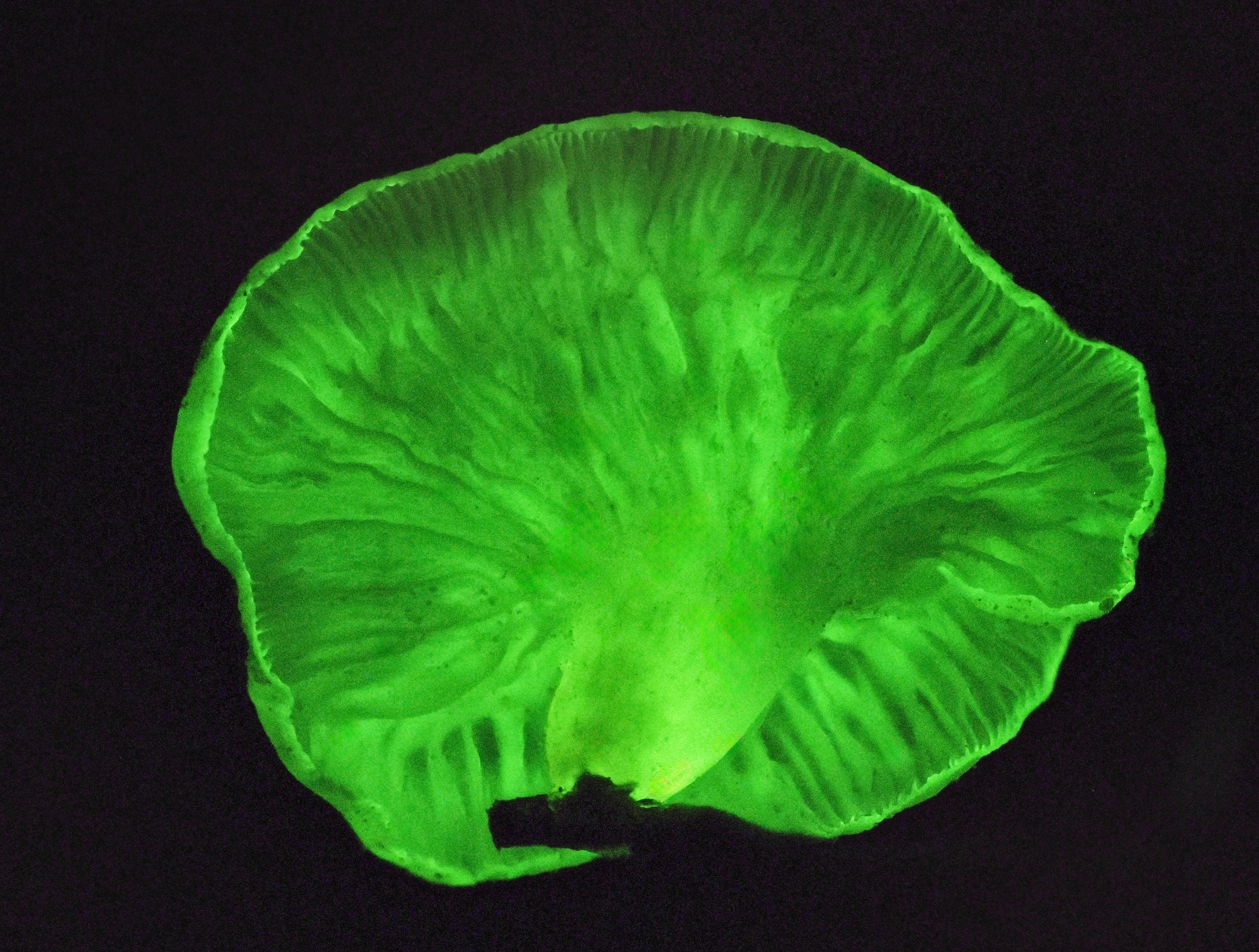

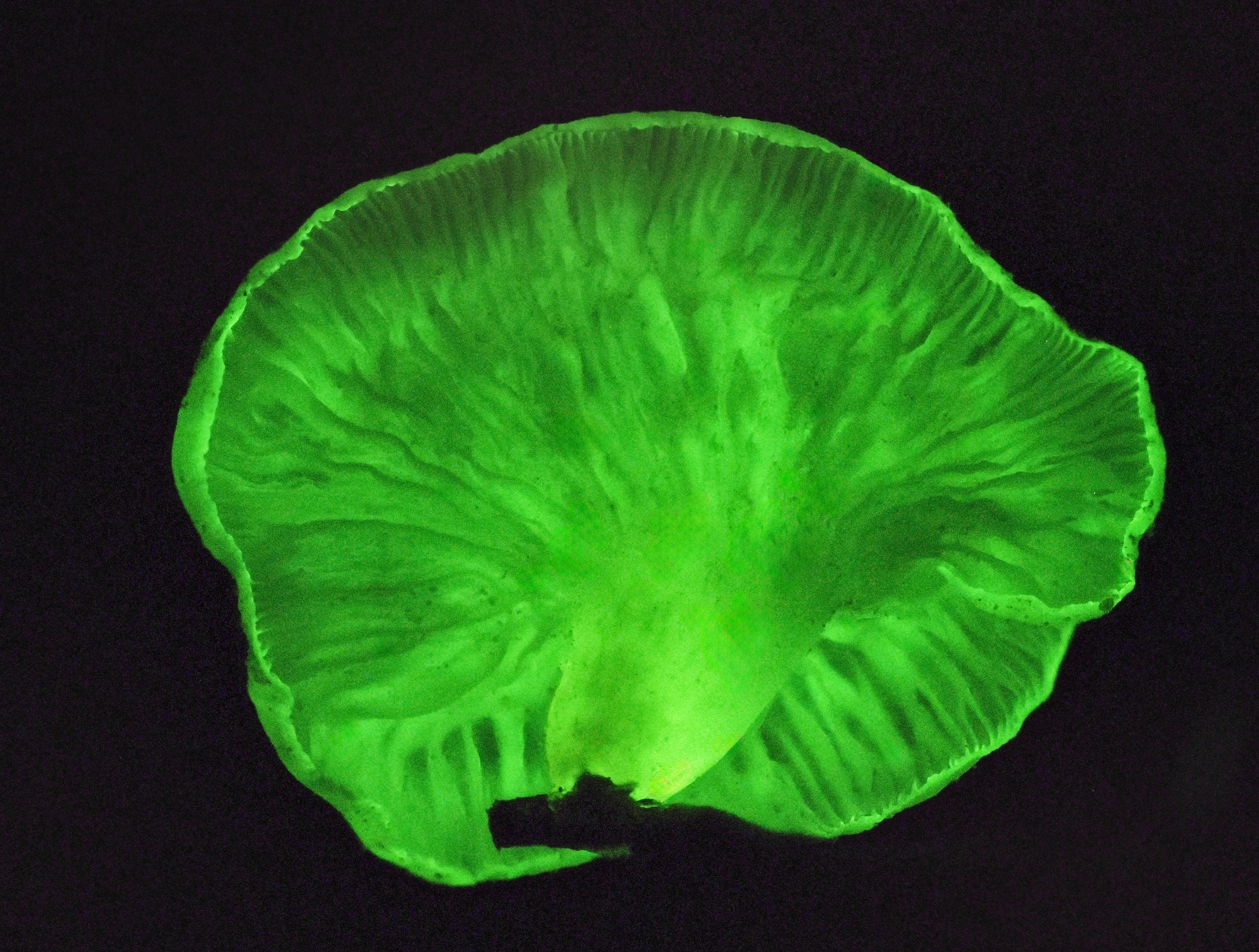

Fungi

Species in the genera Armillaria, Mycena, Omphalotus, and others emit usually greenish light

from the mycelium, cap and gills. This may attract night-flying insects and aid in spore dispersal.

Ecological Functions

The uses of bioluminescence by animals include counterillumination camouflage, mimicry of other animals

to lure prey, and signaling to other individuals of the same species, such as to attract mates.

Steven Haddock et al. list definite functions in marine organisms: defensive functions of startle,

counterillumination, misdirection, distractive body parts, burglar alarm, and warning; offensive functions

of lure, stun or confuse prey, illuminate prey, and mate attraction.

Counterillumination Camouflage

In many animals of the deep sea, including several squid species, bacterial bioluminescence is used

for camouflage by counterillumination, in which the animal matches the overhead environmental light

as seen from below. Photoreceptors control the illumination to match the brightness of the background.

Attraction

Fireflies use light to attract mates. In the marine environment, use of luminescence for mate attraction

is chiefly known among ostracods, small shrimp-like crustaceans. A polychaete worm, the Bermuda fireworm

creates a brief display, a few nights after the full moon, when the female lights up to attract males.

Defense

Some squid and small crustaceans use bioluminescent chemical mixtures or bacterial slurries in the same

way as many squid use ink. A cloud of luminescent material is expelled, distracting or repelling a potential

predator, while the animal escapes to safety.

Mimicry

Bioluminescence is used by a variety of animals to mimic other species. The cookiecutter shark uses

bioluminescence to camouflage its underside by counter-illumination, but a small patch remains dark,

appearing as a small fish to lure larger predatory fish.

Human Applications

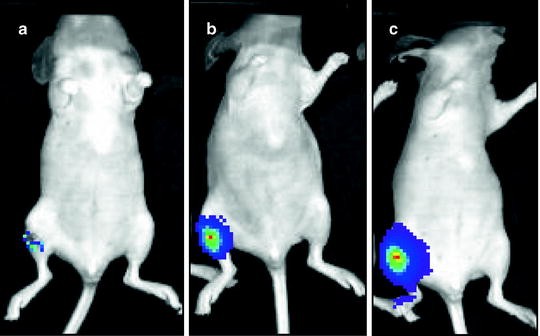

Bioluminescent organisms are a target for many areas of research. Luciferase systems are widely used in

genetic engineering as reporter genes, and for biomedical research using bioluminescence imaging.

Discovery

Green Fluorescent Protein (1961)

Osamu Shimomura discovered and isolated green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish

Aequorea victoria. This groundbreaking discovery would later win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

in 2008, shared with Martin Chalfie and Roger Y. Tsien for their development of GFP as a tool

for biological research.

Engineering

Genetic Applications (1986)

The firefly luciferase gene was first used for research using transgenic tobacco plants.

This marked the beginning of widespread use of luciferase-based systems as reporter genes

to track gene expression in real-time, revolutionizing molecular biology research.

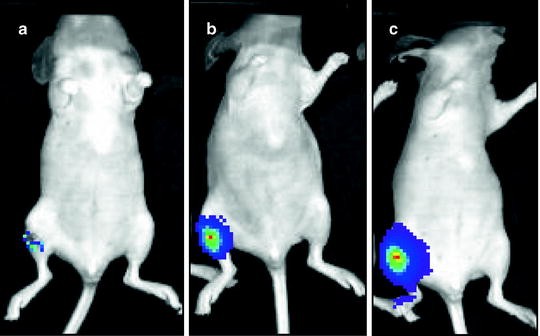

Medicine

Medical Research & Imaging

Bioluminescence imaging became widely adopted for non-invasive tracking of cellular processes

and disease progression in living organisms. Researchers began exploring bioluminescent activated

destruction as an experimental cancer treatment, opening new possibilities in targeted therapy.

Lighting

Sustainable Solutions (2016)

Glowee, a French company, started selling bioluminescent lights for shop fronts and street signs.

This pioneering effort demonstrated that engineered bioluminescence could one day be used to

reduce the need for traditional street lighting, offering an eco-friendly alternative.

Innovation

Glowing Plants (2020)

In April 2020, scientists successfully genetically engineered plants to glow more brightly

using genes from the bioluminescent mushroom Neonothopanus nambi. These plants convert

caffeic acid into luciferin, creating self-sustaining bioluminescent organisms.